In this second part of my series on Julian Assange ( (see Meeting Julian Assange again for the first time) I begin to explore some of the perceptions and accusations against him widely circulated in the press. The three main accusations that we hear about are that Assange committed rape, that he colluded with Russia, and that he didn’t redact the material he published through WikiLeaks and so put lives at risk. Another that I hear on occasion—that without Assange, Donald Trump would not have become the US president, is a crime far more serious than all the others put together for some people I know!

In this post, I explore the accusation that has profoundly influenced the broader public perception of Assange—that he is guilty of rape. The media storm around this allegation sharply turned public opinion against him, and I believe that it helped to create a background climate of hostility that has provided sanction for some of the more heinous treatment he received and the ‘lawfare’ waged against and Wikileaks by US intelligence agencies.

In researching the sex allegations against Assange, I looked mostly at the public record of testimonies and a few media interviews. I tried to steer clear of opinion pieces on the story, preferring to form my own impressions from sources that presented the facts of the case with the minimum of editorializing. It was interesting to observe how many seemed to have already made up their minds right out of the gate . I cannot claim to have uncovered the ‘truth’ about what really happened during that fateful Swedish summer, but what I learned has raised a lot of questions for me around the motives, sincerity and credibility of certain individuals involved, as well as the curation of the image of Assange as a dangerous sexual predator.

Like many of you, I was shocked by the headlines back in late 2010 that two Swedish woman had accused Julian Assange of rape. Among the many things that I didn’t know until recently is that the two women in question did not go to the police to report that they had been raped or sexually molested in any way. They did not even consider themselves to be victims of a crime. According to their own testimonies one of the women went to the police to see if she could make Assange get an STD test and the other went with her—at least initially—to provide moral support.

The story is confusing, convoluted and often contradictory, but probably not wildly more so than any other sex triangle story, with the inevitable conflicting emotional and sexual agendas. So I’ll start with what we do know with at least some degree of certainty, and that is what the women in question themselves shared with the investigating authorities, and later to the media.

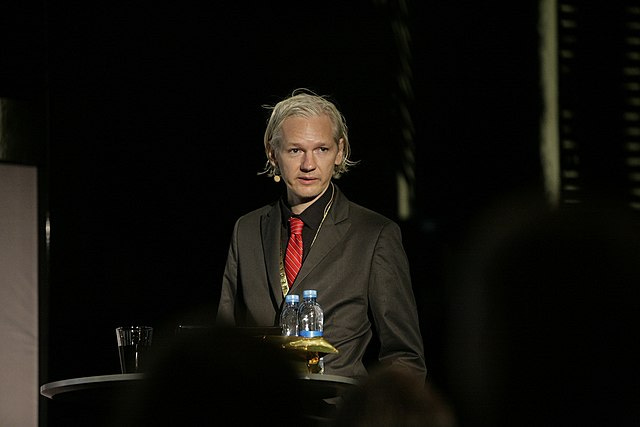

Julian Assange in November 2009 at a media conference in Copenhagen.

In August 2010, Julian Assange was visiting Sweden to speak at a conference. The conference organizer, 31 year old feminist academic, Anna Ardin, invited him to stay at her flat. Ardin admits that she was interested in having sex with Assange, mostly as an act of revenge on her ex-boyfriend, but was upset at his reluctance to use a condom, accusing him of tampering with it and then claiming that it had broken. She said that he was sexually aggressive and that afterwards she had felt “humiliated and abused”. She later told Swedish media that she never felt afraid of Assange, adding that “Julian is definitely not a monster but he crossed my boundaries.”

That night Ardin hosted a traditional Swedish “crayfish party” at her flat in Assange’s honor. A Twitter post, which some say she had tried to erase, apparently described her delight at hosting a party for one of “the world’s coolest people.”

It was at the party that Ardin confided what had happened the previous night to some of the female guests. Two days later, 26-year-old photographer, Sofia Wilen, who had met Assange at the event that Ardin had organized, contacted Assange to meet up. They ended up back at Wilen’s flat where she says they had consensual sex but that things got uncomfortable the next morning when Assange initiated sex with her while she was still sleeping and without wearing a condom. Wilen phoned Assange to ask him to get an STD test but he replied that he didn’t have time. When Wilen next spoke to Ardin the two women shared their experiences and decided to go to the police to see if they could somehow legally pressure Assange take an STD test.

The story certainly has unsavory elements, and I don’t think that anyone can or should defend Assange’s sexual behavior, but even in its worst interpretation it does not add up to what we had all been led to believe. It was not rape. It was reported that Anna Ardin had accused Assange of sexual assault and that Sofia Wilen had accused him of rape, (though at the time the women’s names had not yet been published). And yet, according to an extensive report on the allegations by Nils Melzer, former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, Wilen stopped cooperating with the police and refused to sign her statement once she realized that they intended to press charges. In a text, Wilen apparently wrote that while she did not want to be party to any criminal charges against Julian Assange, “the police were keen on getting their hands on him”.

The truth is obviously a lot more complex than the sensationalistic press coverage as even Ardin admits in her tell-all book In the Shadow of Assange. (Ardin also published an online guide on how to exact revenge on cheating boyfriends called Seven Steps to Legal Revenge which is about as mature as it sounds). Critics of Ardin have pointed out that throwing a party for someone who sexually abused you the night before is weird to say the least, while her supporters say that none of these details matter. Abuse is abuse, period. For their part, Assange’s British lawyers didn’t do their client any favors by calling the allegations against him “sex by surprise” which sound patently ridiculous.

I must admit that I struggled with some of the contradictions in Anna Ardin’s story. For example, she said that while having sex with Assange she’d had “one orgasm, perhaps even two” but she also described the experience as “the world’s worst screw”. She submitted as evidence a condom that she claimed was worn and torn while they had intercourse, but no DNA of either her or Assange could be found.

Unsurprisingly, there are all kinds of rumors about Anna Ardin herself, one being that the Cuban government ejected her from the country on suspicion of being a CIA agent. The CIA rumor is part of the “honeytrap” theory—that the sex allegations were all a plot to smear Assange’s reputation. I couldn’t find any credible journalist who takes this theory seriously, publicly at least, but it’s a great plot twist for the Netflix series.

Having heard the testimonies from the two women and considered all the evidence, it only took Sweden’s chief public prosecutor, Eva Finne, five days to dismiss the allegation of rape, stating, “I do not think there is reason to suspect that [Assange] has committed rape,” concluding that his actions towards Sonia Wilen “disclosed no crime at all”.

Yet the following month, Sweden’s director of public prosecutions, Marianne Ny, reopened the investigation and reinstated all the original charges in their strongest form; suspicion of rape, three cases of sexual molestation and unlawful coercion. A European arrest warrant was then issued with the rape charge lowered to ‘rape of a lesser degree’ as the result of an appeals court ruling. When even the Swedish prosecution had dismissed the rape charges, it is hard to understand where they came from all of a sudden. Sofia Wilen never put her name to any statement that accused Assange of rape. Anna Ardin publicly stated that she had not been the victim of rape in a Twitter post in 2013.

Melzer acknowledges that there are serious sexual offences that exist outside of the definition of rape, but wrote that there are “strong indications” that the ‘rape’ accusation—the gravest of them all—was manufactured. He suggests that the Swedish legal authorities “deliberately manipulated and pressured [at least one of the alleged victims]…into making a statement which could be used to arrest Mr. Assange on the suspicion of rape.” He goes on to posit the claim that the Swedish police “revised” Wilen’s statement “to better fit the crime of “rape” before it was resubmitted by a third Social Democrat politician to a different prosecutor who was prepared to re-open the case.” That prosecutor was Marianne Ny.

Ny eventually closed the investigation after almost 7 years, but the damage had been done. Assange consistently denied all the allegations but was never completely exonerated. By the time the case was officially closed for the last time, his reputation and credibility were in tatters and he had lost a great deal of support amongst his former allies.

The Swedish Prosecution Authority opened and closed the investigation three times between 2010 and 2019. A lot was made of the fact that Assange refused to travel from the England to Sweden for questioning, which some took as an indication of his guilt. Assange had been questioned by Swedish police in August 2010, but his lack of cooperation with the investigation thereafter did not endear him to the public. A lawyer for the Crown Prosecution Service, the public agency tasked with criminal prosecutions in England and Wales, wrote to Ny, advising that she interview Assange “only on his surrender to Sweden.” Assange was eventually interviewed again in 2016 in the Embassy of Ecuador, but the Swedes were not allowed to question him directly or ask follow up questions and the interview was conducted through an Ecuadorian prosecutor.

It seems that Assange’s lawyers had advised him against going to Sweden for fear that it would lead to his extradition to the United States, where he would be at the mercy of a government that is documented to have plotted to assassinate him. Sweden’s extradition treaty with the US is technically only for individuals suspected of murder, but the Swedish government reserves the right to decide extradition cases outside of the European Union, and there was no guarantee that Julian Assange would not have been subject to further extradition to the USA had he gone there.

The investigation was kept artificially open for several years, but there never was any ‘case’. After Julian Assange’s arrest and removal from the embassy of Ecuador in 2019, it was widely reported that a new Swedish prosecutor had opened the investigation once again but since there was no evidence to move the process forward it simply fizzled out. During the course of the investigations into the sex allegations against Assange, no less than forty violations of due process were exposed, including active manipulation of evidence.

Italian journalist, Stefana Maurizi, the author of a book defending WikiLeaks, Secret Power, doggedly filed FOI requests over several years to try to establish why the investigations kept on closing and opening like a stuck elevator. Why had they frozen at the preliminary stage for so long, giving the impression that an actual case was being built? Her research was hampered by the fact that the Crown Prosecution Authority and the Swedish Prosecution Authority had both inexplicably destroyed a large portion of their email exchanges. Ultimately, Maurizi became convinced that this story had been used “to destroy [Assange’s] reputation, his credibility, and focus the public’s attention on a rape case that never was.”

Is there truth to the claim that these investigations were manipulated through external pressures in order to keep the accusations in the public eye? There were certainly enough people very upset with Assange by this point. Only one month before the sex allegations hit the headlines, Wikileaks had published thousands of internal military logs exposing US operations in the middle east in collaboration with some of the biggest names in international media.

In short, there never were any rape charges filed against Assange. Of all the labels you can throw at him “rapist” is not one of them. It didn’t need to be true though, did it? The accusation was enough to make an already complicated and not especially sympathetic figure, persona non grata in many people’s eyes.

I still tend to believe women who accuse men of rape for the simple reasons that rape is so prevalent and sexual assault victims are so often not believed and their suffering so often minimalized. But I have to say that delving into the Julian Assange story will forever make me wary of highly publicized sex allegations against those whom powerful governments have in their crosshairs.